Updated on 2020-11-12 by Adam Hardy

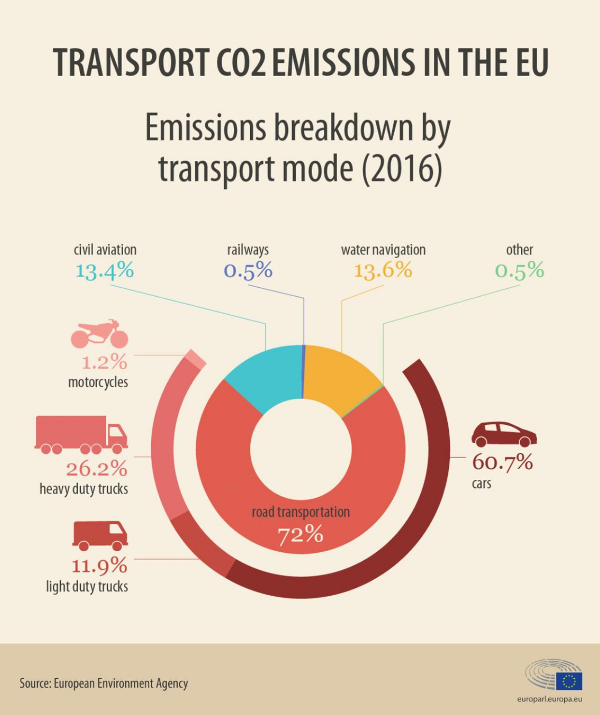

In the USA, the UK and the countries of western Europe, about 80% of adults own a car. These must all become electric vehicles in short order if the world is to avoid catastrophic climate change – the figures below show why. After 3 or 4 generations in everyday life, the car is now embedded in western culture. Most trips are made by car and the automobile industry is planning to produce another 3 billion units over the next two decades.

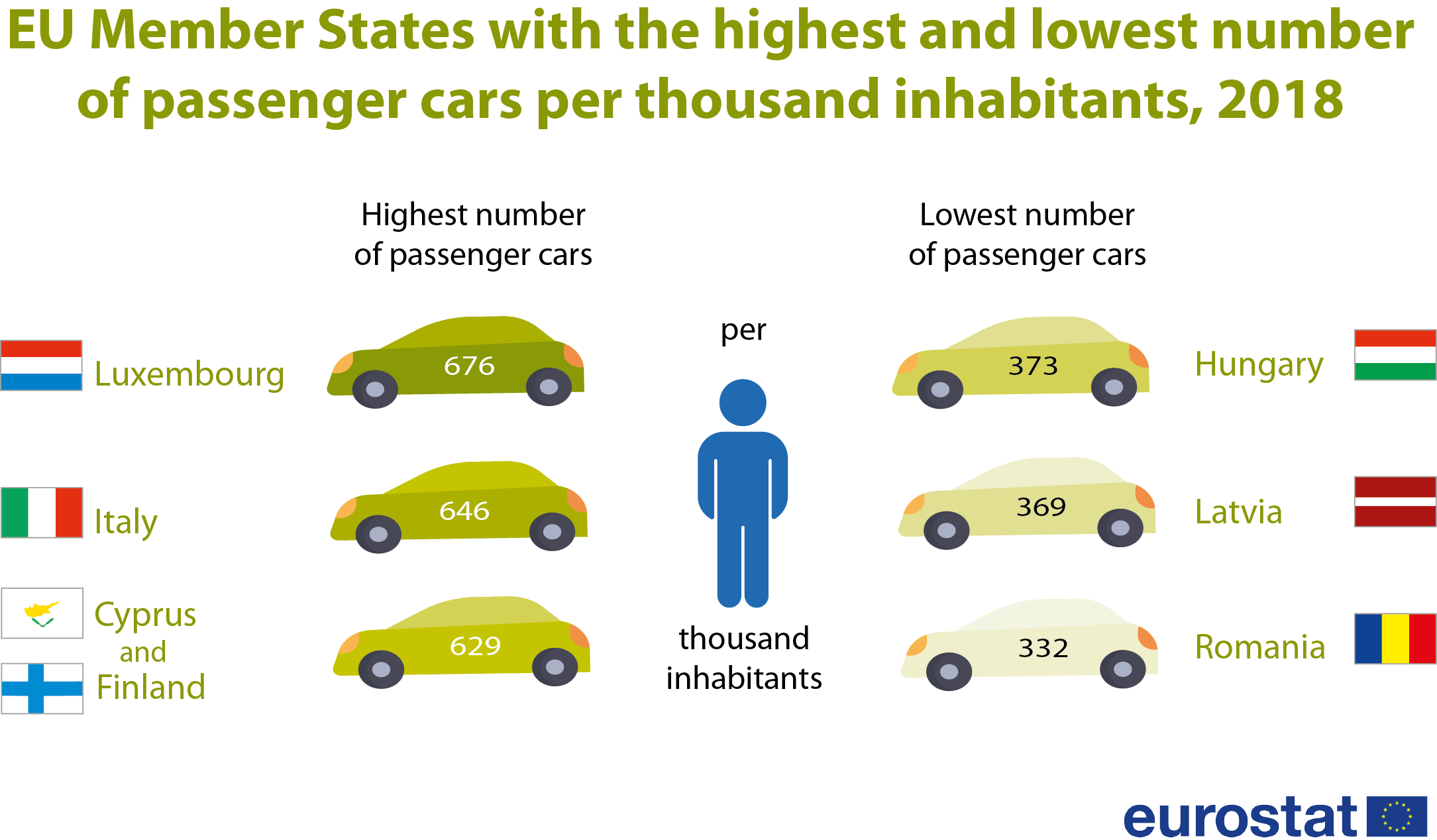

The problem with that is the rising CO2 emissions and global warming it causes. Transportation makes up 14% of all CO2 emissions globally.

That transportation figure from the US EPA includes aviation, shipping, rail and road.

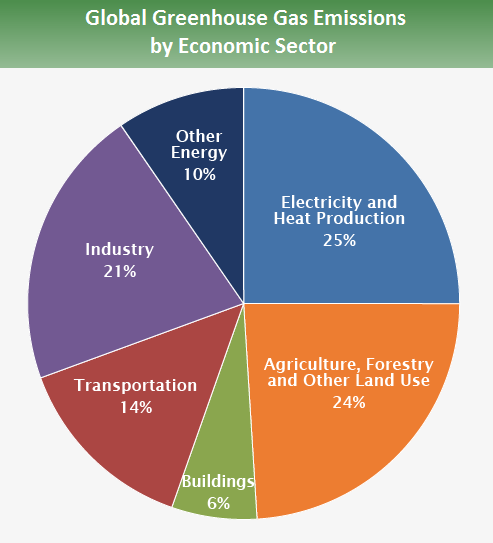

This EU-based analysis shows personal transport emissions makes up 60% of all transport. Generalising massively then, domestic car use accounts for roughly 8% of global emissions. The obvious solution put forward by the likes of Elon Musk for instance is to replace all petrol and diesel engine cars with electric vehicles. Now add to that the 3 billion extra cars that car manufacturers see as necessary to meet future demand!

3 Billion Electric Vehicles

Yet society runs on the automobile, especially in America. The USA has been built for the car. But in the UK and Europe and many older towns and cities in the US like Boston, cars fill the streets and roads sometimes to breaking point. If the traffic isn’t too bad a problem, then parking can be. It can take ages to find a parking space in a residential neighbourhood and it often involves driving around until one becomes free.

Imagine for a moment that climate change has been solved and these are all electric vehicles. Not only is parking an issue, but the car has to be charged too. In a typical city street, a house will have 3 or 4 apartments and each set of residents will own a car. There would be charging cables everywhere, dangling out of windows, strewn across pavements, causing street-wide outages as people overload the local power grid. The image is comical.

How easy it could have been if Renault and Toyota’s collaboration on replacable batteries had won general acceptance and been used as standard for all EVs. Petrol stations across the world could have taken up the task and the change would have been minimal. But that is not how big business works.

So officers in planning departments across the world have been busy thinking up solutions. There are pop-up charge points, placed at regular intervals down the street.

There are armadillos, geckos and limpets – an assortment of newly invented charging hubs that live on the kerbside – and there are lamppost-based charging points, fast hubs and induction pads, all of which are powered from the grid with card-based payment.

The London borough of Greenwich is running a pilot project based around lamppost chargers.

Dundee in Scotland is tackling the problem differently – it is rolling out fast charging hubs in key areas which could comfortably cater for 15% of the city’s traffic in 2020 (far more than the current number of electric vehicles), and fits in well with Scotland’s national target to ban the sale of petrol or diesel-engined cars by 2032.

In the States, the nationwide EV charging network Electrify America has just succeeded in creating a carbon offsetting scheme based on charging rates for their EV chargers across the country, which means they can profit from selling carbon offsets as well as electricity. The validation and verification of the offsetting scheme ensures that only offsets are sold when renewable energy is used.

I wrote about the city of Lahti in Finland where the city pledged in 2017 to achieve carbon neutrality by 2025. After making great strides decarbonising everything that their city government could, Lahti the city is now pretty much carbon neutral, and the CO2 emissions come mainly from individuals’ choices.

Lahti isn’t worried about shipping or aviation or built-in emissions in imported goods – such things are really not in their remit as a city council. What is on their radar is domestic car use. This can be measured and potentially reduced by smart planning and policies. So Lahti is investing heavily in a personal carbon trading scheme as a way to coax people out of their cars and into alternative transport modes. They don’t foresee enough uptake of electric vehicles to achieve their target by conversion to EVs. They are investing in urban transit, cycling and pedestrianisation, and are optimistic about hitting that carbon neutral target.

A third option exists too, as featured in the documentary film 2040.

Much like the big tech companies Google and Tesla, film-maker Damon Gameau rejects the idea that everybody has to have a car – including the citizens of India and China – and that car ownership doesn’t have to sky-rocket by another 3 billion over the next 2 decades. Driver-less cars run by networks like Uber can serve the needs of the population far better than when the streets and motorways are clogged by an unfeasible number of cars.

Tesla is also planning to become an energy supplier to the UK national grid to utilise all the car batteries sitting idle or on charge by Tesla owners. I wrote about V2G (vehicle-to-grid) and other renewable energy storage issues here: The Energy Storage Issue.

But can people give up their cars? At a rough guess at least half if not 3/4 of car owners probably can’t imagine life without one – under current circumstances. If cities and councils are worried about the problems now, then they need to start thinking beyond the simple provision of charging points, and start providing alternative modes of transport that will make the car seem less like an absolute requirement and something more like a nice-to-have and something that might not be worth it if parking and charging it are so hard. It seems the Finns are ahead of the game.

The UK has 2035 in its sights for the phase-out of petrol and diesel car sales. The UK Parliament’s All-Party Parliamentary Group for Renewable and Sustainable Energy is putting together policy for the EV infrastructure, and it looks like they have yet to decide which direction they’re going to take. They just published the optimistically titled piece “Ending the Sale of Petrol and Diesel Vehicles by 2030”, which was written by the managing director of Centrica.