Extreme weather, floods and wildfires on top of stories about melting polar ice-sheets should trigger a sense of impending doom in any psychologically healthy individual. Global warming’s impact on the human psyche is a very recent thing, at least in the UK, despite the fact that the United Nations has been fighting climate change for 30 years. It is only in the last 5 years that people in wealthy nations have perceived themselves to be victims of the climate crisis.

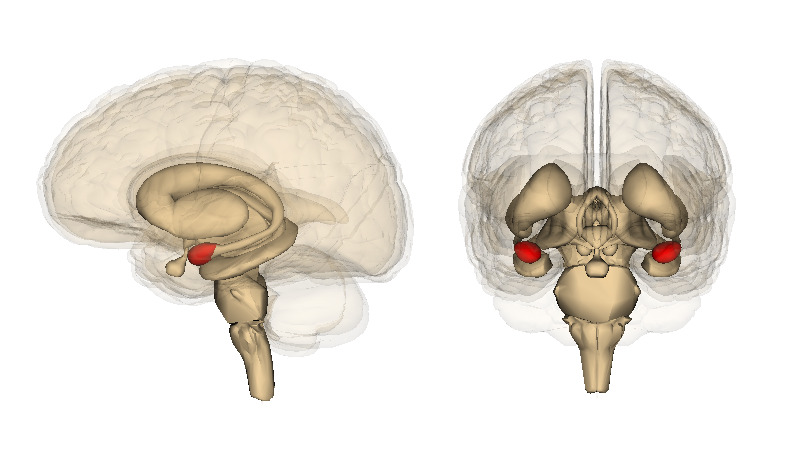

At least to this author though, this sense of impending doom is not a sign from God that the End Times are here. Neuroscientifically, it is a signal from our subconscious mind to our rational mind. This is one of the responsibilities of the amygdala, insula, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex, working together to evaluate the significance of new information that filters into our subconsious. This is how our intuitive responses arise.

These signals (feelings of impending doom) are picked up consciously by the dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex, where all the rational thinking goes on. Humans evolved this way to come up with plans and action. We can’t hit climate change with a stick, so our intuition comes up with this signal, a feeling to instruct our conscious mind to come up with a response, and urgently. Obviously there is scope for us to panic instead or suppress it, but in optimal circumstances, our rational mind would work out an action plan and the feeling would subside.

Now with the advent of swift climate attribution studies from meteorology labs around the world, science can pin the blame on global warming, or declare its innocence, for any extreme weather event.

An event such as the Pacific Northwest 2021 heatwave is still rare or extremely rare in today’s climate, yet would be virtually impossible without human-caused climate change

World Weather Attribution Service[1]Western North American extreme heat virtually impossible without human-caused climate change

The result is that this sense of impending doom will now occur on a steady but intermittent basis. Should the climate science show an acceleration in its frequency, then the psychological signals will heighten in intensity.

Climate change made 2022’s UK heatwave ‘at least 10 times more likely’

Carbon Brief[2]Climate change made 2022’s UK heatwave ‘at least 10 times more likely’

Despite the supercomputers and complex algorithms, the maths behind climate attribution studies only works in hindsight. It doesn’t help predict the extreme weather or wildfires or flooding. This is essentially just weather and subject to the same unpredictability and vagaries as every newshour weather forecast. That it will happen again is certain, but where and when can never be predicted.

The Ahr Tal flooding in 2021 (184 dead in Germany) up to 9 times more likely due to climate change

World Weather Attribution Service[3]Heavy rainfall which led to severe flooding in Western Europe made more likely by climate change

Extreme weather has been a blind spot in the minds of economists right up to the time of writing. Economics professor Steve Keen[4]One of EcoCore’s supporters – see About published a detailed critique of mainstream economists and specifically the Nobel Prize-winning Prof. William Nordhaus, who seemed to have suffered a complete lapse of imagination:

[Nordhaus] assumes that about 90% of GDP will be unaffected by climate change, because it happens indoors…

Prof Stephen Keen[5]2020 academic paper, The appallingly bad neoclassical economics of climate change

It beggars belief that Nordhaus’s research was deemed worthy of a Nobel Prize. Nordhaus ran cost-benefit analyses that demonstrate how 4°C should be optimal for economic growth over the next 100 years. This thinking dominates all economic research covered by the UN IPCC reports up to and including the Assessment Review 6 published in 2022.

As climate change worsens and extreme weather, wildfires, flooding, drought, crop failures and so on weigh on the economy and chip away the wealth and high standards of living that our western economy brings in the near term, the long term prognosis is becoming clearer to non-scientists in alarming ways that are bound to stoke any person’s feelings of impending doom.

The question now arises of whether mainstream economists are lying awake at night now trying to cope with their own feelings of impending doom. Their work on climate has been shown to be, frankly, appallingly bad, so the thought that the climate scientists might have a case must surely have occurred to them. It’s not easy to see, with economics being the branch of academia that it is. While there are signs that mainstream economics is absorbing elements of Keen’s work, there hasn’t been the kind of new dawn that the global situation demands.

Meanwhile the Potsdam Climate Institute among others has built global climate models which highlight the boundaries of Earth’s current, stable, human-friendly climate. The models highlight the dangers and consequences of breaching those boundaries. Potsdam Professor Johan Rockström highlights the issue in these videos.

Some IPCC climatologists are now collaborating with experts in other fields to point out that the economic claim that 4°C of global warming is “optimal” contradicts key findings from Earth systems research. Geo-physical changes on a 4°C warmer planet bring implicit socio-economic impacts, to the extent that even non-economists foresee significant risk of economic collapse.[6]Keen, Lenton, Garrett, Grasselli 2022 “Estimates of economic and environmental damages from tipping points cannot be reconciled with the scientific literature”

A growing sense of impending doom

Existential fear of the imminent destruction of civilisation is exacerbated by the difficulty that climate scientists have of putting probabilities on such outcomes. The planet’s tipping points are not only very difficult to model and predict on their own, but their mutual interaction is very under-researched and an order of magnitude more difficult to model. It would hardly be surprising if climate scientists themselves are the hardest hit by feelings of impending doom, to a degree which could amount to PTSD.

The Minefield Metaphor

After years of fighting for his reputation against vicious fossil fuel-funded disinformation campaigns, Professor Michael E. Mann, a renowned climatologist, won’t be drawn on possible futures or impending doom. In a masterclass in mind management, he steadfastly reiterates that the way forward is to cut fossil fuel usage and invest heavily in renewable energy.

Rather than the common metaphor of society hurtling towards the edge of a cliff beyond which our doom awaits us, he lays out a picture of the future as minefield we have stumbled into. This is particularly appropriate in the absence of clear risks associated with individual or collective tipping points. The metaphor can also be extended to illustrate the dangers of exceeding 1.5°C with the intention of man-made global cooling to bring temperatures back down to safer levels in future. “It’s a minefield” as the saying goes, and engineering a safe exit is just as dangerous as ploughing into it in the first place.

Fear is the mind killer

Frank Herbert, Dune.

Please indulge the Frank Herbert quote. Difficult or easy as it may seem, avoiding or exiting that climate crisis minefield is a noble goal, and adopting that goal is the perfect antidote to fear. On a psychological level, taking climate action helps reduce one’s perception of uncertainty, it brings a sense of control, and it allows us to paint a more positive picture of ourselves and our social group.

A psychological precondition in the human psyche for the alleviation of the feelings of impending doom, or any anxiety, is that the plan of action is credible. For many people, reducing their personal CO2 emissions in itself isn’t a credible plan. EcoCore promotes it as part of a package of actions that include personal behaviour change, watching the impact of your money, communicating in your peer group and workplace, protesting, and political advocacy for an economic system based on carbon allowances that works on a national and global scale, a policy that would bring benefits not just to ordinary people, but to business and industry, to government and to the rest of the world as well.

References

| ↑1 | Western North American extreme heat virtually impossible without human-caused climate change |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Climate change made 2022’s UK heatwave ‘at least 10 times more likely’ |

| ↑3 | Heavy rainfall which led to severe flooding in Western Europe made more likely by climate change |

| ↑4 | One of EcoCore’s supporters – see About |

| ↑5 | 2020 academic paper, The appallingly bad neoclassical economics of climate change |

| ↑6 | Keen, Lenton, Garrett, Grasselli 2022 “Estimates of economic and environmental damages from tipping points cannot be reconciled with the scientific literature” |