The question of how to control methane emissions has been seriously neglected, and the situation is deteriorating. Methane is eighty times worse than CO2 for the climate, but cows, sheep, goats, rice paddies, disused coal mines, escaped or vented fossil fuel company leakages, shipping diesel non-combusted exhaust, and Russian/Ukrainian terrorist acts all emit high levels of methane. Under the carbon accounts framework using a carbon currency and carbon allowances, there are ways to make methane emissions extremely unfavourable for the people or companies responsible – save the acts of terrorism.

If the methane emissions are consistent and predictable, as they are for agricultural practices such as cattle farming, then the local government can license the activities with licences paid for in carbon tokens. Scottish beef cattle for instance produce around 70kg methane per year, which in CO2e is 2,000kg. Since carbon tokens are denominated in kilos of carbon, that licence would cost the farmer 2,000 tokens every year.

To balance the farm’s carbon account, the farmer would have to recoup the tokens by charging an appropriate carbon price for the sale of the cattle or its products. If the average highland cattle is slaughtered at 3 years of age, then the total lifetime methane CO2e is 6,000kg, i.e. the total licence costs that the farmer paid to rear the animal.

The butcher would pay carbon tokens for the animal at the slaughter house, and demand tokens on the sale of its meat.

Assuming the cattle weighs 500kg on the hoof, and the butcher can turn the carcass into 250kg of meat, the butcher must sell each kilo of beef for 24kg of carbon tokens. A 200g/8oz steak would cost 4.80kg tokens.

If the carbon accounts system was introduced with a personal carbon allowance set at the current average in the UK of 12 tonnes of CO2 per year, that would be roughly 230kg of tokens per week. A loaf of bread would cost 1 token. Filling up a petrol ICE car would cost 138 tokens, because 1 litre of petrol emits 2.3kg CO2 at a carbon price of 2.3 tokens.

People would probably be deterred from driving petrol cars a lot more than they would be deterred from meat – initially. As the personal carbon allowance is shrunk in order to reduce the amount of fossil fuels extracted and burnt, this story could change.

Fugitive Methane Emissions

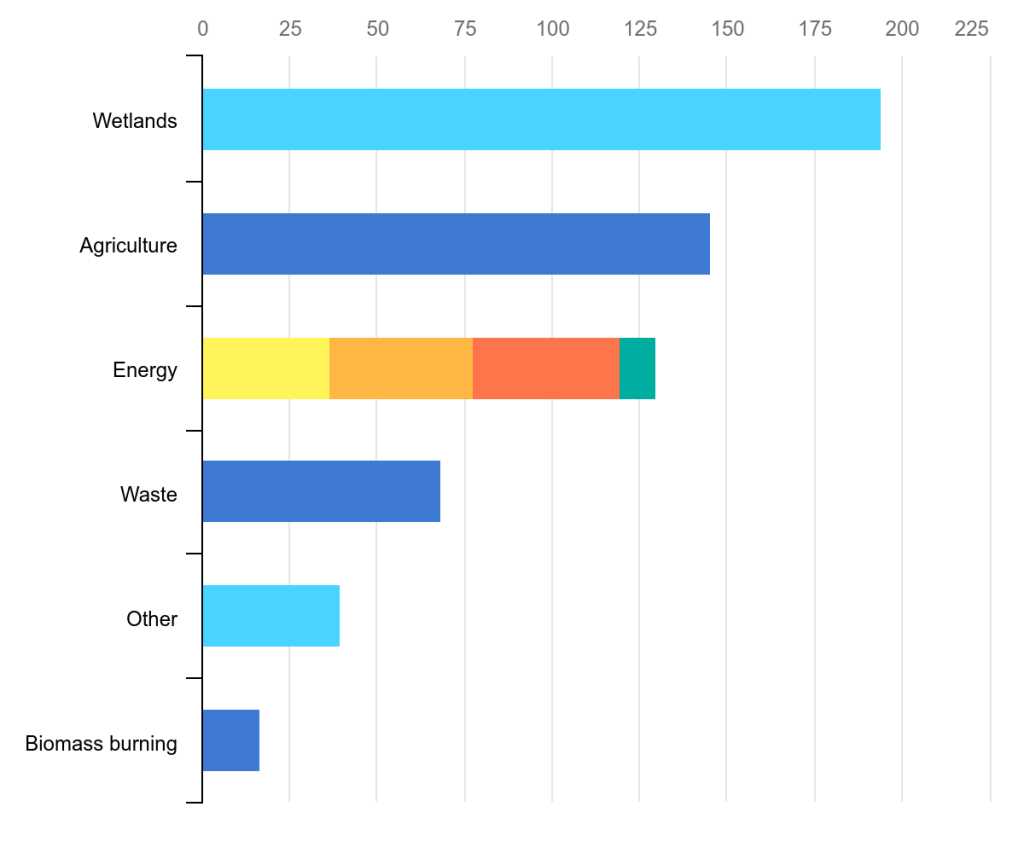

However only 24% of global methane emissions come from agriculture. 32% is natural, from marshland for instance, and 22% is from the fossil fuel industry partly deliberately, partly accidentally releasing it in their extraction activities. There is a lot of debate around these numbers and it has taken investigative journalism, atmospheric physics and satellite imagery to at least partially uncover what is going on.

Many fossil fuel operations will vent methane because:

- the operation is not prepared to capture the large amounts of methane being extracted

- it does not have the on-site infrastructure to burn it off, turning it into CO2 – not ideal but better than methane

- it requires investment to shut the site down and seal it safely and properly but the company refuses

- an accident happens

Some of these are low level, long term incidents. There are a large number of disused or abandoned gas wells and coal mines across the planet which slowly but steadily emit vast amounts of methane.

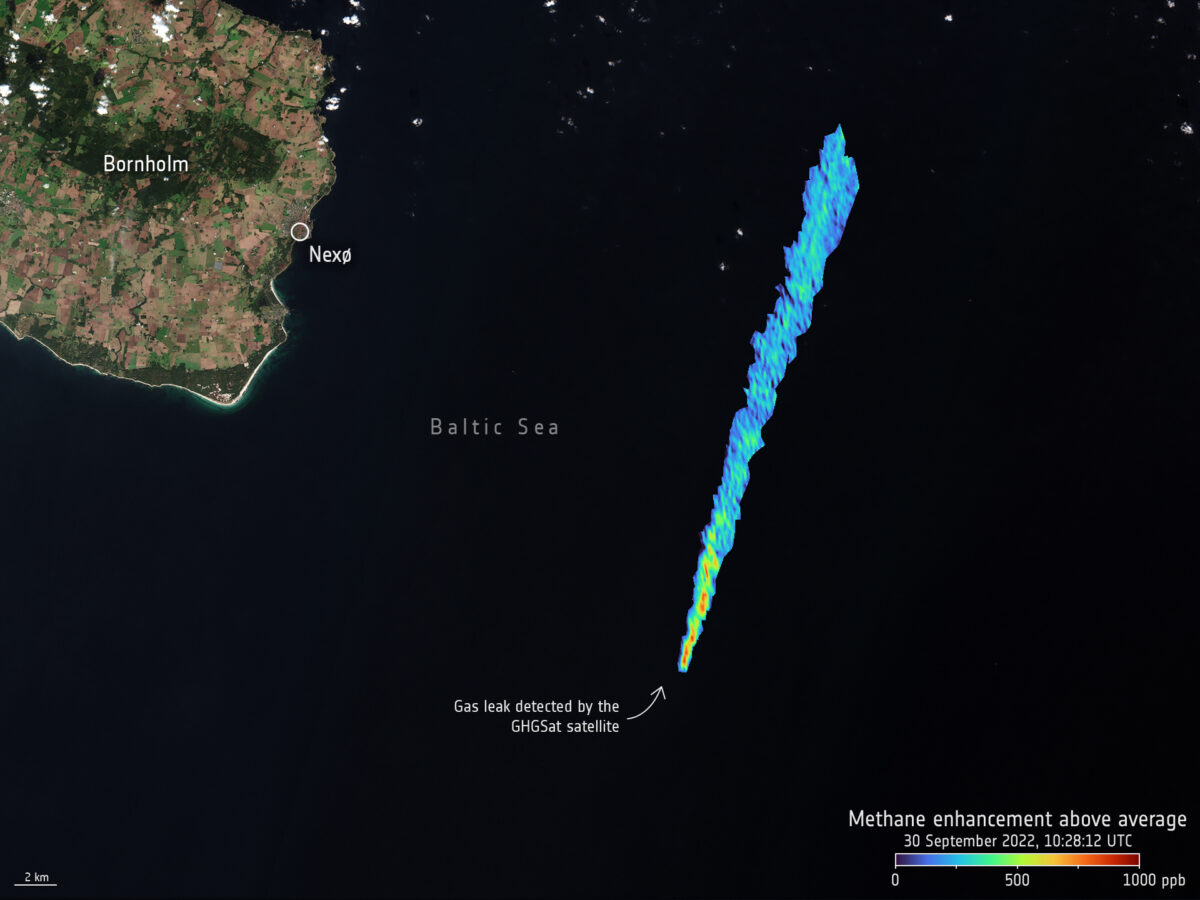

Some accidents on the other hand are one-off events known as super-emitters which can be detected by satellite from space or by journalists with infrared cameras. Some are just phenomenal, releasing over 100,000 tonnes of methane, the equivalent of almost 3 megatonnes of CO2. In Texas, a US state which declines to implement many federal fossil fuel industry regulations properly, a fossil fuel company might routinely emit methane in the order of 50,000 tonnes CO2e per year.

Under the carbon accounts framework, the Central Carbon Bank which administers the system would also need an enforcement agency to monitor such methane releases and apply after-the-fact penalties for the leakages. These penalties would be priced in carbon tokens equivalent to the amount of methane released. If the agency used satellite imagery to pinpoint methane venting from a particular fossil fuel company, as in the example above, of 50,000 tons of CO2e, that would be the amount of the penalty. If the carbon price were in the region of $100 per tonne, the company would be looking at a bill to the tune of $5,000,000.

It’s not difficult to see how such methane pollution would quickly cease to be a routine occurrence.

More Resources on How to Control Methane

Scottish Rural College document: https://www.nfus.org.uk/userfiles/images/Policy/ELU/0720%20Methane%20Factsheet.pdf

NASA’s data on methane: https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/methane/

International Energy Agency’s summary: https://www.iea.org/reports/methane-tracker-2020/methane-from-oil-gas

Carbon Brief’s opinion: https://www.carbonbrief.org/methane-emissions-from-fossil-fuels-severely-underestimated/

The scale of the venting problem, an article in Associated Press: https://apnews.com/article/science-texas-trending-news-climate-and-environment-0eb6880f7c4532a845155a3bd44c2e4b