Updated on 2025-04-25 by Adam Hardy

Contraction and Convergence of national CO2 emissions levels, C&C for short in COP circles, was until 2010 the policy basis behind climate negotiations to make a fair deal between all nations for a global approach to CO2 emissions reduction. That is the reason why it may be time to give the policy a good dusting-off.

But our personal carbon footprint – what would not be emitted if we did not exist – might actually occur anywhere in the world. The globalisation of our individual CO2 emissions was one of the reasons Contraction and Convergence was abandoned in favour of the each-nation’s-best-effort approach of the 2015 Paris Climate Accord’s Nationally Determined Contributions system.

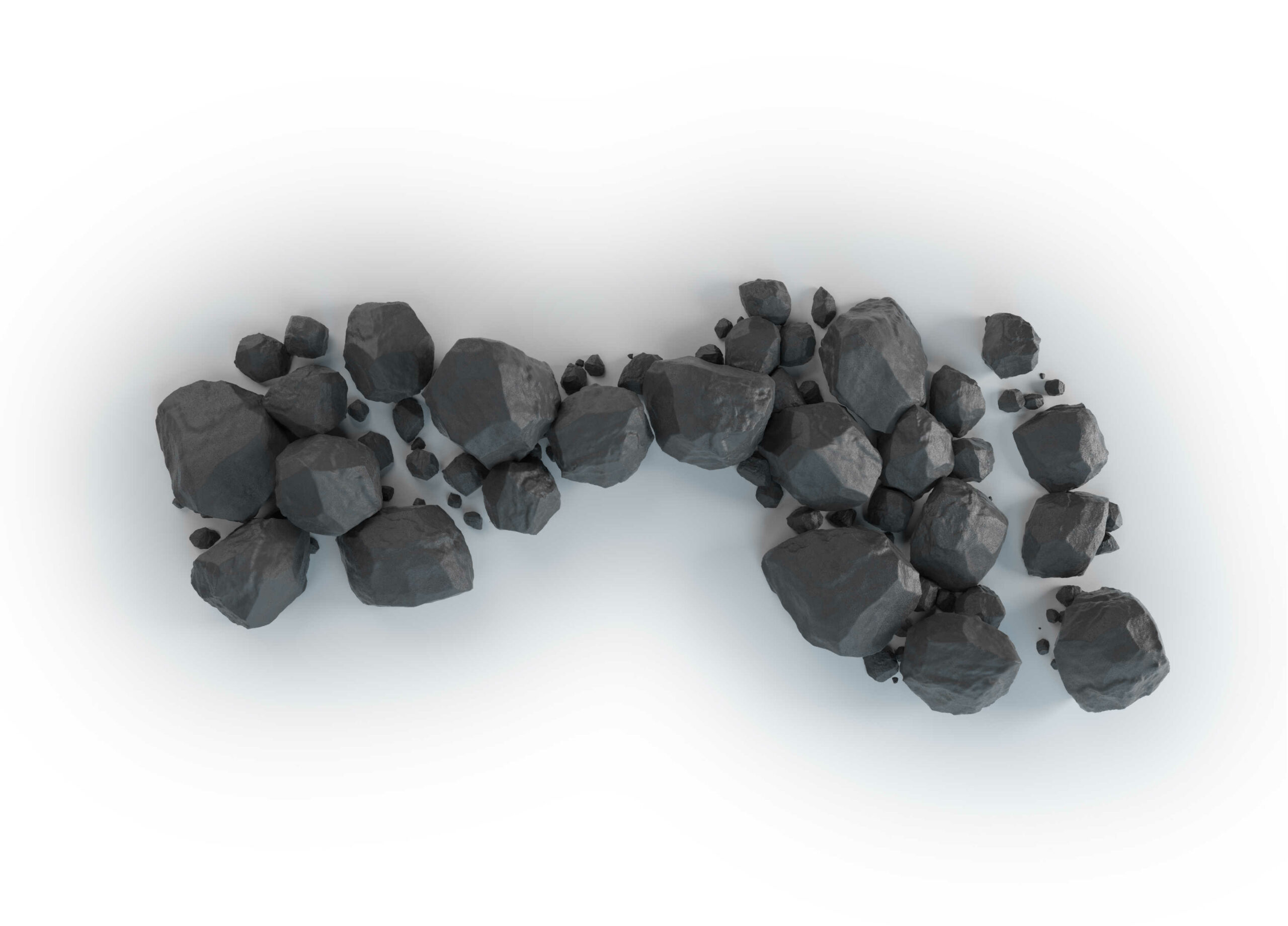

Under Contraction and Convergence, the global carbon budget or pie – what emissions all nations agree should be allowed – is divided up by nations in way that they agree is fair and equitable. The graphic below shows how such a global deal would lead to near-zero carbon emissions in all countries:

- the top chart displays how individual per capita emissions from citizens of different nations must converge.

- the time axis starts in the year 2000 when this policy was considered the necessary basis of any future UNFCCC climate treaty.

- the lower chart shows the growth of global CO2 emissions, peaking in the year 2027, colour-coded by nation. A fine idea at the time.

Contraction and Convergence of CO2 Emissions

In theory, all countries would agree on a total global CO2 emissions figure for the next year. This annual amount would then be decreased year on year. This is the “Contraction” part of the framework.

To make the treaty fair, countries which had emitted the most would start reduction immediately.

Other countries would be allowed to carry on expanding their CO2 emissions (e.g. the blue swathe in the chart above) until an agreed cut-off date. This is the “Convergence”. By the cut-off date, all countries’ citizens will have reached the same per capita carbon footprint. This allows for technology transfer, infrastructure build, and generally a slower, less expensive energy transition for those countries with less resources.

This chart was created with climate data from the year 2000. The numbers on the axes now look very different, but the principle remains the same.

A Socially Equitable Approach

One huge elephant-in-the-room problem with the 2015 Paris Agreement is that it doesn’t define how to reach its global goal. Since it now appears that the terms of the Paris Agreement are not being met, and that taking action on CO2 emissions reduction is becoming more and more urgent, one obvious way forward is for a coalition of the willing to adopt a climate target, using a global carbon budget for a specific scenario. 2°C of global warming, for instance.

The global carbon budget provides a known quantity of CO2 that may be emitted to stay within target. This is the carbon pie which countries divide up amongst themselves by treaty, the limit that their citizens and industry may emit. This establishes a level of fairness internationally.

On the national level, allocating the national carbon budget to citizens on an equal per capita basis would ensure a socially equitable outcome. Implementation of the EcoCore Carbon Accounts concept would enhance that further, because it allows trading between those with ‘high’ footprints and ‘low’ footprints. This exchange creates a cash flow from the rich who typically have high footprints to the non-rich. On an international level, with trading between citizens of the UK and Malawi for instance, the equitability advantage becomes even more obvious.